“Today we received a beautiful gift from you… we cannot find the words to describe it…”

Dick Budig gets cards in the mail with these kinds of sentiments on a fairly consistent basis. He doesn’t really know the woman who sent him this letter, in fact, he’s never even met her… but he recently painted a portrait of her deceased son.

Over the past 16 years, painting portraits of men and women killed in war has become Dick’s hobby. He does his work completely free of charge, seeking to honor the families of these heroes and thank them for their sacrifice.

It’s work that satisfies his soul, and it’s a job he created because he saw a need that was unmet – both in the community and in his own heart.

“I’ll be 80 this month,” Dick said, looking over his glasses. “I’ve been around a while.”

He’s seen a lot, done a lot and all of it, he said, has shaped why he’s painting portraits of fallen heroes.

As a child of the ’40s, Dick said he remembers the big events of World War 2. He remembers hearing about Hitler marching into Poland, saying goodbye to his relatives who went off to fight and the look on his parents’ faces when they opened a telegram telling them their family members weren’t coming home.

He and his friends played ‘war’ endlessly, making up creative skits and scenarios that mimicked what they heard war was like overseas. But the reality of war was also very apparent to Dick, even at the age of 10. He said he missed his relatives who died in the war, and not getting a chance to say goodbye seemed wrong.

When Dick got older, he went into the military as well. Serving as a member of the Air Force, his days were spent on a SAC base where his unit guarded planes between the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam.

It wasn’t as bad as other wars, he said. However, there was no guarantee that he or his buddies would be coming back from war – but he did.

Dick came home to his wife and two young children and they settled in his hometown of McCook, Nebraska. Here, he attended a community college where he was a pre-med student, until he realized he couldn’t hack chemistry. He changed his degree to journalism and worked for the McCook newspaper for a few years.

But after a while, Dick said he couldn’t sit at his desk and pound on his typewriter anymore. He moved his family to Lincoln, where he transitioned from journalism to advertising. From there, his work history gets complicated.

“I did a thousand little things,” Dick said with a laugh.

He was a hairdresser, journalist, owned an advertising agency, gold refinery, jewelry design shop, an ice cream shop and eventually a pawn shop.

At one point, he looked into buying a bank, but couldn’t afford it, and soon realized a pawn shop functioned a lot like a “poor man’s bank.”

Dick spent his days tinkering with broken electronics, fixing them up and selling them for a profit. He did so well, in fact, that he was able to pursue one of his long-term passions that he’d since put on the back burner – painting.

As a kid, Dick was always drawing. He would spend hours sitting and sketching, and one day he added color to his work, opening his eyes to the world of painting.

But with a family, there was little time to paint professionally or even pursue it as a hobby. He needed to make money, and art wasn’t a viable option for feeding his family.

After Dick retired in 2000, he circled back to painting. He’d always loved portraits and began to make time to pursue his art. He realized that he needed people to paint, and who better to paint than fallen heroes, he thought.

When he started out, families were a little skeptical of his work, and understandably so. He said oftentimes families were still mourning their loved ones and couldn’t fathom someone offering to paint a portrait free of charge, but Dick’s offer was truly that simple and sincere.

He’s starting to lose track, but Dick said he’s painted somewhere in the neighborhood of 150 portraits of fallen war heroes. He started out painting just Nebraska soldiers, but said he can’t say ‘no’ to families.

When parents contact him they often share a lot about their child with him – their likes, dislikes, character traits and personality and even how they passed away.

“They tell you these stories and it’s difficult,” he said. “These kids are gone, just gone. But there’s still something magic about an oil painting I think…”

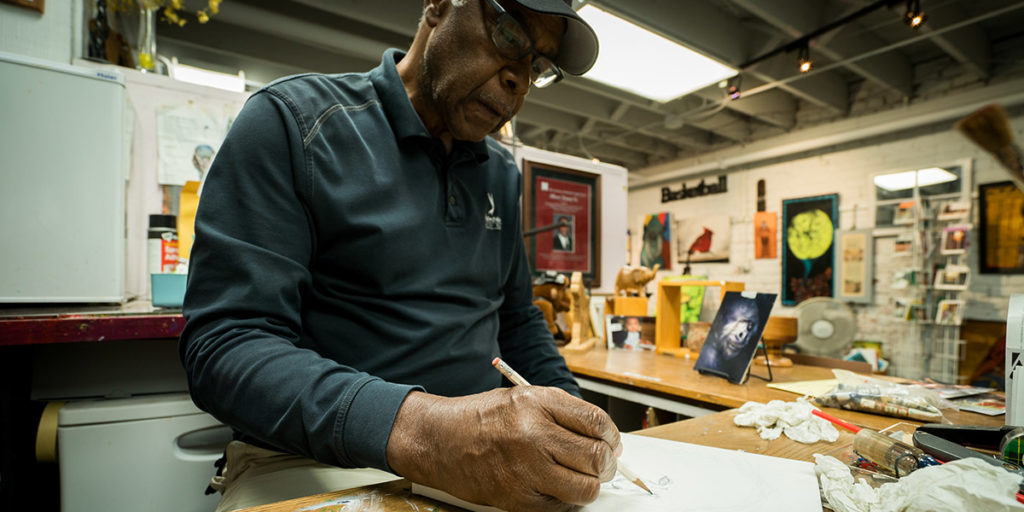

When he paints, he doesn’t think about the soldier’s story or even their family, he thinks about the mechanics of what he’s doing. The colors he’s using, the detail and shading – every detail needs to be just right. Dick said when he paints, it’s like times stops and it’s wonderful.

Some portraits take him a few days, others can take up to a month to complete, and when a painting is done the family either comes to pick it up from his studio or Dick sends them the portrait in the mail.

“People come in here to see the portrait and they just stand here and weep,” he said. “And I get some really nice cards.”

He pulled a few pieces of paper out of a stack, “These are some of my favorites.”

Written in pencil on lined notebook paper were notes from two young girls whose father was killed in the Middle East. They dotted their ‘I’s’ with hearts and told Mr. Dick how he was their favorite artist because of the portrait he’d painted of their father.

‘This is better than money,” he said, holding up the letters. “You can’t buy this.”

Dick’s story has become about giving stories back to families. He knows that a big reason he paints portraits is because it’s his own way of mourning the loss of his family members. But it’s also allowed him to step into the lives of families from across the country. To sit with them in their pain, hear their story and give them something to remember.

He may just be painting portraits, but to the families who receive his work, Dick is their hero.