She wasn’t sure she wanted to share her story. Actually, she felt like she didn’t really have one. She says the people she works with, they have the “real” story.

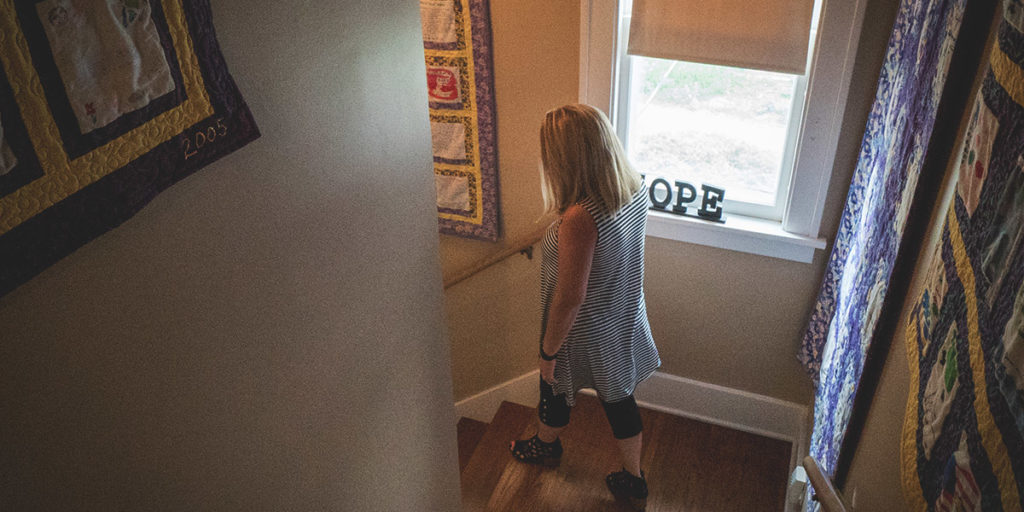

As the executive director of the Mourning Hope Grief Center, Carly Woythaler-Runestad has seen and heard a lot of stories. She’s not a grief group facilitator and she doesn’t lead any of the sessions, but she is the one who’s responsible for keeping the lights on and the programs running at Mourning Hope.

It’s a job that she ‘fell’ into in many senses, but it’s become her greatest passion and something that’s helped her define her own story.

Carly grew up in a rural town in central Iowa. It was a small, community-focused place where she was surrounded by strong parents, impactful mentors and experienced a nurturing upbringing. This environment seemed to set the tone for Carly’s life.

She attended the University of Iowa and received her undergraduate degree before going on to work as a music therapist and then the director of a long-term care facility. Carly decided to return to school to earn her Master’s degree in health care administration and then put her degree to work as a lobbyist for the Nebraska Hospital Association.

Carly had several jobs after she graduated that she liked and was good at, but each one seemed more like stepping stones rather than a place to settle down and dig in. She felt like she was constantly searching for the right fit, and started to think maybe it didn’t exist.

She and her husband moved to Nebraska in 2004 and a few years later Carly’s life was shifted by major changes and transitions. Her mother was battling cancer, her grandparents died and she experienced a miscarriage – all of which happened in a relatively short period of time.

The sudden losses and change caused Carly to re-evaluate her story, to start thinking about who she was, what she wanted to do and who she wanted to be. She realized she wanted a job that she was excited to go to every day, a place where she could see the impact of her work and was more than just a way to utilize her skills and take home a paycheck.

It was during this period of transition that Carly came across the Mourning Hope Grief Center.

She started out as a part time employee who was interested in the center’s mission of helping kids and their caregivers navigate seasons of loss. Carly watched broken, unsure and scared kids and caregivers walk through the front door of Mourning Hope, only to see them leave with hope and excitement.

It’s work that’s nearly addictive because of the noticeable impact it has on families, and Carly said it didn’t take long before she stopped seeing Mourning Hope as a stepping stone to something bigger… it became her landing place.

The work got under her skin in the best way possible and opened her eyes to a population of the city and state that she hadn’t seen before. Mourning Hope’s mission became her mission as she dug in and found her place.

It’s heavy work, but Carly wouldn’t have it any other way. The stories of the kids and families from Mourning Hope seem to play on a continuous loop in her mind, motivating her to work harder, do more and send emails at nearly all hours of the day.

They are the reason she loves waking up and going to work.

They are the reason she’s worked to join local and national organizations to advocate for grieving children and families.

And they are the reason she’s an engaged wife and mother who values every minute with her family.

People often ask Carly if she experienced a significant loss that kick-started her passion, but that’s not why she joined the team at Mourning Hope. She joined because she discovered a deep desire to help others.

As she looks back on her educational and career path, Carly can see that caring well for others has been a theme in her jobs and her story. It’s part of who she is, and something she’s always valued, but working at Mourning Hope brought that to the surface.

Carly said that for so long it felt like she was searching for her story, for what was next and where she wanted to invest her energy and time. Now, ‘what’s next’ looks like staying put, raising her family and being diligent in her work.

She referenced the quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson that says: “To know even one life has breathed easier because you have lived. This is to have succeeded.”

That’s what she wants in life, to live her story well by helping shoulder the burdens of others. For the first time in a long time Carly isn’t looking for what’s next, it’s right in front of her, and her story has never seemed so clear.