“Let me get you that book. It has a whole bunch of stuff about 1923 in it,’’ he says as he shuffles around his cozy east-Lincoln home.

Bob Stuart is looking for a book about the year he was born.

Beginning life in a small apartment above the College View Post Office, Bob was the only child of a flight instructor father and a school teacher mother.

In his 93 years of life, Bob studied architecture, helped run a family auto dealership, served in the Navy, got married, had two children, moved to California, sold real estate and retired back to Nebraska.

Throughout all of that, there has been one constant. Airplanes.

You might say that Bob’s interest in planes is genetic and began with his father.

“I remember my dad and some of his friends bought a real airplane kit and built it in our basement,” Bob said.

He smiles as he tells the story of his father’s first bi-plane.

“One day my Dad asked me if I wanted to go up with him. I was only six years old and a little hesitant,’’ he said.

But it only took a few moments of sitting in the cockpit for the curious six-year-old boy to agree to go.

Bob and his father flew all over Lincoln that day: up 48th, down O street and back up 13th street. But the highlight of the trip was circling the still-under-construction capitol building a few times before heading back to the airport.

Bob was hooked.

He soon became known as the “airport pest” and took every opportunity to hang around his Dad, airports and airplanes. “You couldn’t keep me out of a plane,” he said.

Bob’s dad went on to flight school, became a pilot, mechanic and flight instructor. Then in the middle of it all, started a Chevrolet auto dealership and mechanics garage. The dealership quickly became a family business when Bob’s mother left her teaching career and joined her husband to be the bookkeeper.

Bob helped out too, as much as he could while attending Lincoln High School. It was during that time that he had a sobering accident while riding his scooter one morning on the way to school.

“I was probably going too fast,” Bob sighs as he explains how he laid the scooter on its side to avoid a car that was going to hit him. He slid and spun a few times before hitting his head, hard.

Bob’s injuries were serious and he spent several weeks in the hospital recovering from a concussion that left him with chronic headaches.

Even so, a year later when all of his friends were getting motorcycles, Bob asked his parents about getting one too. His Dad quickly rejected the idea and suggested he think about buying an airplane instead.

Bob was disappointed he couldn’t have a motorcycle, but he liked the idea of having his own airplane. At 19 years old, Bob bought his very first plane for only $395.

“It was a nice red 40 horsepower CP40 Portfield that could really go,” Bob recalls. “It had a top speed of 80 miles per hour!”

Bob’s dad made sure Bob took all of the right precautions and taught him everything he knew about flying. On one occasion, his Dad was helping him learn how to fly with a yoke instead of a stick for controls and when they were preparing to land, the wind started to pick up.

His dad had some difficulty getting the plane stabilized and bounced a few times on the runway before Bob took control. He wanted to show his dad how it was done. After a clean approach and smooth landing, his dad just muttered,”You better mind your own business kid.”

It wasn’t long after Bob learned to fly that the United States joined WWII and young men everywhere were being drafted to serve in the war. Right away, Bob’s dad was called upon to help instruct new pilots in the Army.

Bob was called up to serve too, but because of his head injury, he was initially declared not fit for service. However, after several calls and physicals, he was sent to California to join the Navy. Bob only served a few months before his head injury was discovered and he was sent home again.

Throughout the rest of the war, Bob lived at home, sold cars and helped his mother manage the dealership and garage. Eventually the war ended, his father came home and life went back to normal.

Then one weekend, Bob was serving as the best man at a friend’s wedding when he fell for the maid of honor. He called her up a short time later for a date and the two hit it off.

After dating for six months, Bob and Betty were married in May of 1946. Bob continued to work for the family dealership and the happy couple lived in his parent’s basement while they saved the $6,000 they needed to build their first home. But they wouldn’t stay in Lincoln forever.

Bob had come down with pneumonia several times and a doctor recommended the family move to a different climate if Bob wanted to live long enough to see old age.

“We didn’t have much of a plan,” Bob said. “But we knew a few people out there already.”

Soon, Bob, Betty and their two daughters packed everything up and made the long trip out to California.

Bob began a career selling real estate and while he didn’t own a plane anymore, he still found time to rent one from time to time and go flying with friends.

In 1988 at the age of 65, Bob retired from real estate and moved back with his wife to their hometown of Lincoln, Nebraska.

They both wanted to be close to family and old friends, but Bob admits that his story gets a little dull after the retirement move back to Lincoln.

This last year, Bob and his wife celebrated 70 years of marriage and still live in the cozy ranch they bought when they first moved back.

At 93, Bob is facing the reality of slowing down. “These old legs don’t work like they used to,” he laughs as he complains about old age. When asked about the last time he flew a plane, with disappointment and certainty Bob responds with,“1970.”

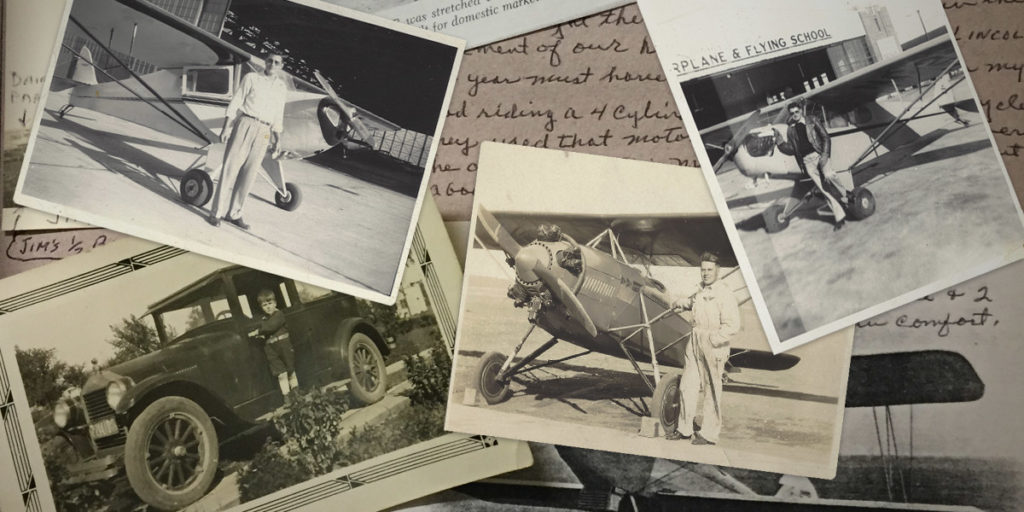

It seems like a long time ago to some of us, but Bob’s memory still keeps a good grasp on those experiences and his basement is filled with catalogs, stories, drawings and old snapshots of planes that either Bob or his father owned.

As he tries to put into words what it feels like to fly, Bob’s eyes light up and he smiles.

“When you’re in the air you can do and go wherever you please. You don’t really have anyone else telling you what to do. You can be your own boss.”

Those could be just the youthful memories of a 93-year-old man or the excited wishes of a six-year-old boy, but what they have in common is what matters most. They both love to fly.